The traditional school year in the United States and much of the rest of the world has been faulted for inefficiency: surely we could get more learning done, or do the same amount in less time, by simply continuing throughout the year, and not taking the summer off for what the English call the “long vac”. There is little doubt that students often forget over the summer at least some of what they have learned (if they have in fact really learned it) throughout the year. So the annual cycle becomes a matter of two steps forward and one step back, rather than the three continuous steps forward that might have occupied the same time.

There is some truth in such a reflection, and were efficiency the only index of value, it might be an insuperable objection to the summer break. But we humans have an unfortunate tendency to try to maximize those things that we think might lead to the best outcomes without really testing the hypothesis or re-examining it, and I think that in leisure we have the unique opportunity to take ownership of our own ideas — something that I, at least would not part with for mere efficiency.

From my own experiences as a student half a century ago, and as a teacher since, I know that my own intellectual life was not wholly or even chiefly shaped by what was being poured into my intermittently receptive brain. I got some real value from my schooling, to be sure — but it blossomed into ideas that I could claim for my own when I had room and opportunity to maneuver, breathe, reflect on things, and, in short, to play with ideas and to try different approaches to them, and hence to develop my own way of thinking and dealing with ideas. While the classroom provided me with much of the raw materials for thinking, it was my own reworking — analysis and synthesis — of these granular bits that made the ideas and their connections mine. In retrospect, it seems clear to me that all the real landmarks in my own mental growth took place on my own time. Accordingly I strongly believe that room to work on your own ideas without constraint is not a garnish — the cherry on top of an education — it’s its main matter.

At Scholars Online, we have tried to root our approach to learning and the formation of the whole character of the student, both in or out of the virtual classroom, in that reality — to bring to the table some of that element of play, which chiefly honors and expresses the agency of the one engaged in it. In the mix, it is essential to have some unprogrammed time in which to exercise one’s own choices, pursue one’s interests without constraint, merely for the love of doing them. When we take ownership of our own learning, the whole experience is essentially transformed. Taking control of your own learning (or recognizing that you had it all along) is the single most powerful perspective-shift you can achieve. It will pay off in ways both measurable and immeasurable forever after.

Accordingly, we’ve tried to honor the distinction in mode that summertime affords — the relaxation of external constraints to allow a look inward. Some of our courses have extended final exams that can (at the student’s option) take all summer to complete. Our summer courses are framed more with respect to play than to proceeding lock-step through a sequence of externally defined achievements. Our culture regards play as gratuitous, but it is not. The ability (which is mostly a willingness) to play intensely and deliberately is no trifling matter: in fact, it’s the chief delineation between the drudge and the genius. Play is powerful because it is unconstrained, and gives the student the liberty to rise up and own his or her own learning. One of the chief hallmarks of play is that its rewards are intrinsic — if you win a game of chess, your prize is having won the game of chess, not (usually) something else. It is not servile: it it not subjected to some outside goal, or coerced with a system of punishments and rewards. I’ve written about these matters here and here in our blog, and in other places as well.

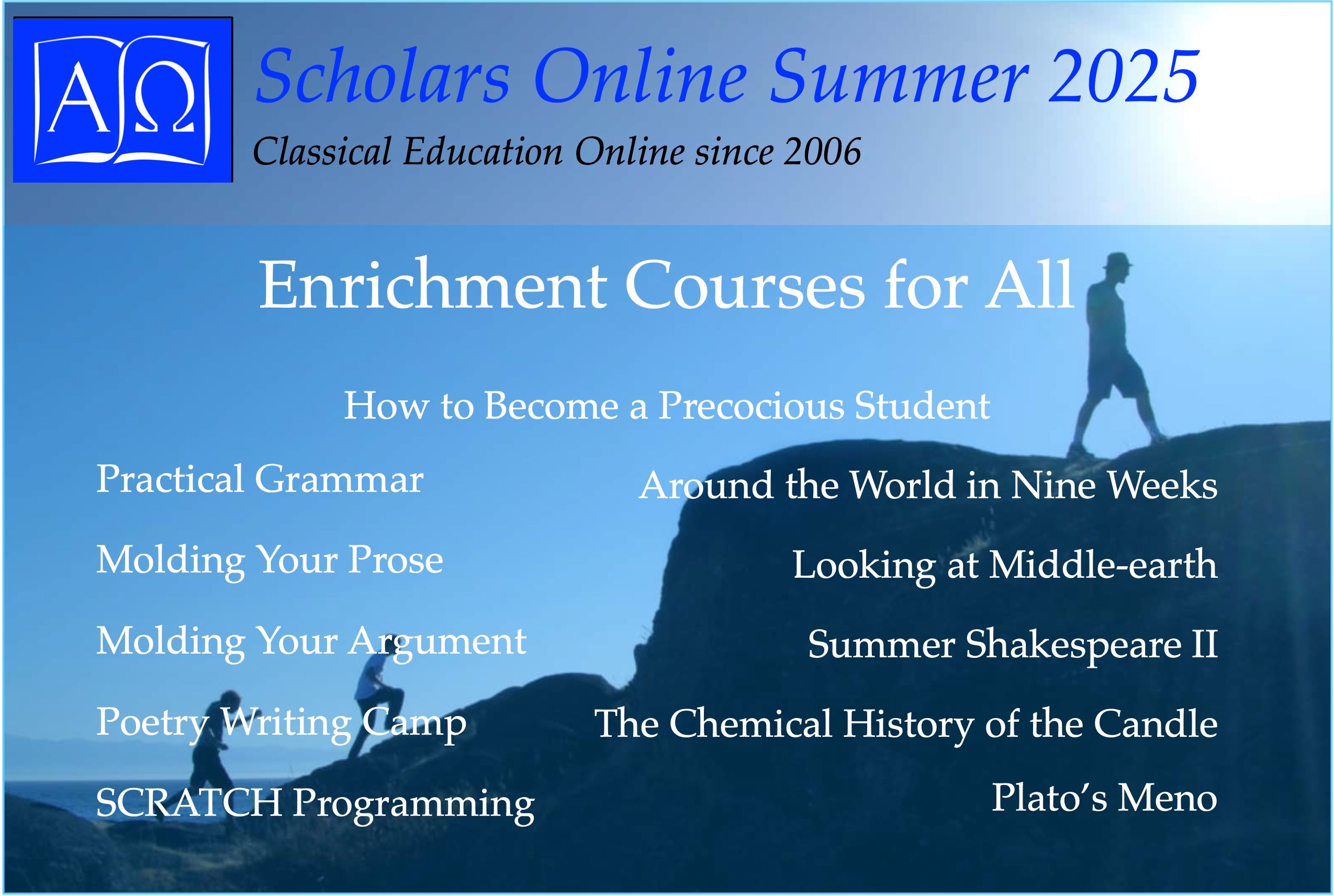

Our summer classes serve several purposes, and they are not really all quite on the same wavelength. Some of them have to do with developing certain skills or sets of skills (Precocious Student, Molding Your Prose, Practical Grammar, etc.). Going through those with attention and engagement will in general improve one’s ability to write and study clearly and effectively. But they are owned by the student, and importantly open-ended: among other things, they can be retaken with profit repeatedly. The courses that cover other specific topics — such as the reading courses (Looking at Middle-earth and the Summer Shakespeare), the science courses (The Chemical History of the Candle or Scratch), the poetry-writing classes (Poetry Writing Camp for youth, Poetry – Advanced Workshop for adults) or the Philosophy classes (Plato’s Meno) — are designed to let students acquire familiarity with the material and work up their own interest on their own time and in their own way, without having to worry about exams, evaluations, or any extrinsic goals. They will also serve as joyful samplers for those considering taking more structured and programmatic courses during the school year. Try one and see whether it’s something you’d like to pursue more systematically, at least now without constraint, just for the love of doing it itself.

Doing something for its own sake is the purest form of learning, and what liberal education is about.