“Call me Ishmael.”

Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick begins with a three-word imperative — one of the most famous openings ever written for a novel. That is it the product not of the late twentieth century, but of the mid-nineteenth, is especially remarkable. Whereas most novels of its day ease the reader into the unfolding story by stages, this one gives us an order, and within a few sentences has set a scene encompassing narrator and reader together, in which the narrator not only tells the reader how to address him, but also insists on silencing our questions.

It’s masterful; it’s cheeky; it’s unlike almost anything else before or since. As a whole Moby-Dick is one of the most daring pieces in the long history of the novel, while at the same time being what one of my English teachers in junior high would have insisted wasn’t a novel at all. For her opinion I am not overly concerned; in the intervening fifty-odd years the use of the term has certainly drifted far from its earlier moorings. That it probably wouldn’t have been considered a novel in the ordinary sense of the term even in its own day is probably more telling. Exactly what it is, though, still confounds those who like to classify everything neatly, and for 170 years it has remained perplexing. The American Heritage Dictionary cites Moby-Dick as an example of allegory; I personally think that it’s not allegory at all. Wiser heads than mine have weighed in on the question, but not all on the same side.

I’ve been teaching Moby-Dick in American Literature for about a quarter of a century now, and of all the fiction I cover it creates the widest swings of opinion. Some students grind through it with impatience and perplexity; others find it the wildest of wild rides. A handful become lifelong devotées, rereading it regularly. Few are indifferent, however.

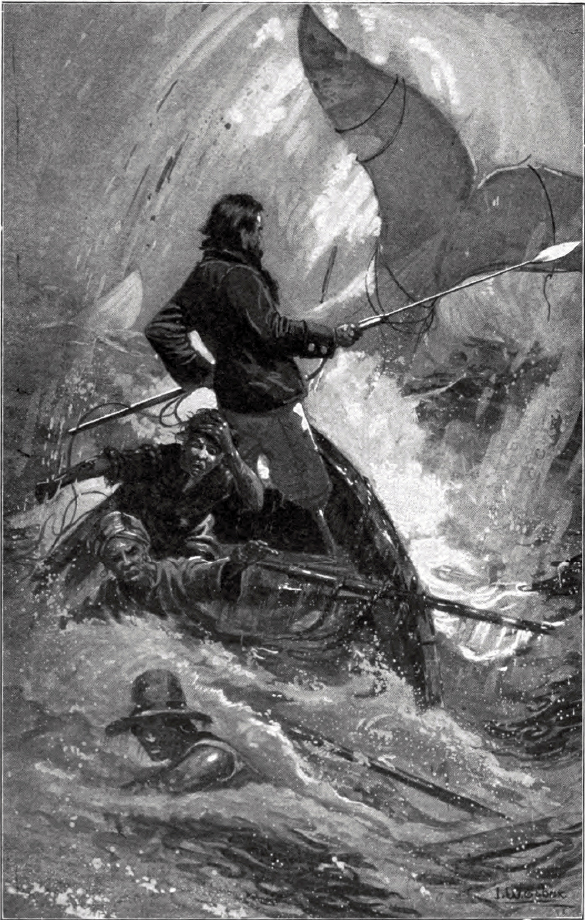

Part of what makes the book so remarkable is its fragmented story-telling, which bounces relentlessly from one place to another. It does not sit still. Having established Ishmael as the narrator (whether that’s his real name or not is open to question), it goes on to narrate his entry to the story, and then takes up scenes at which he is not present. Some chapters are written almost as if they were plays on a Shakespearean model, others as if they were clinical discussions of the mechanics of whaling; one noteworthy chapter (“The Doubloon”) is almost a catalogue of the psychological states of various characters with respect to a single symbol. Some describe a rapid-fire sequence of events; others are generic descriptions of no events at all. The perspective of the book ranges into and out of a theological domain that cannot possibly be considered orthodox, and yet it ends with a quotation from the book of Job. The title figure (I doubt that we can really call the eponymous whale a character) is by turns a vast, almost transcendent force of nature, a symbol, a topic of a variety of authors’ writings, the object of an obsession, and ultimately a kind of blank white sheet on which the reader is challenged to write his or her own underlying interpretation. The book remains a thing of contradictions, and almost nothing else I have ever encountered in my teaching of literature has anything to touch it.

Considered by many to be the quintessentially great American novel, a niche in which it is not entirely comfortable, it was published first in London in October 1851 in three volumes under the title The Whale. It was published about a month later in the United States in a one-volume edition on today’s date (November 14) as Moby-Dick, or The Whale. It received cautiously favorable reviews in England, but encountered a far less enthusiastic audience on this side of the pond. Before Melville died, it had gone out of print, and was widely considered a failure, as were most of his later works. His tortured final masterpiece Billy Budd was never published during his lifetime.

I’m sure there are many reflections to be had about all of that. It’s certainly true that many of the things that have come to be regarded as important cultural landmarks were scarcely recognized in their time; conversely, many things that seem important in their day go down in the long run as a flash in the pan or simply banal and pointless. One of the values of reading challenging literature like this, I would argue, is that it gives us a yardstick by which to measure importance — not necessarily so we can dismiss anything (which is a dangerous exercise), but to linger over something, especially the thing that seems kind of wacky. It might be a diamond in the rough.