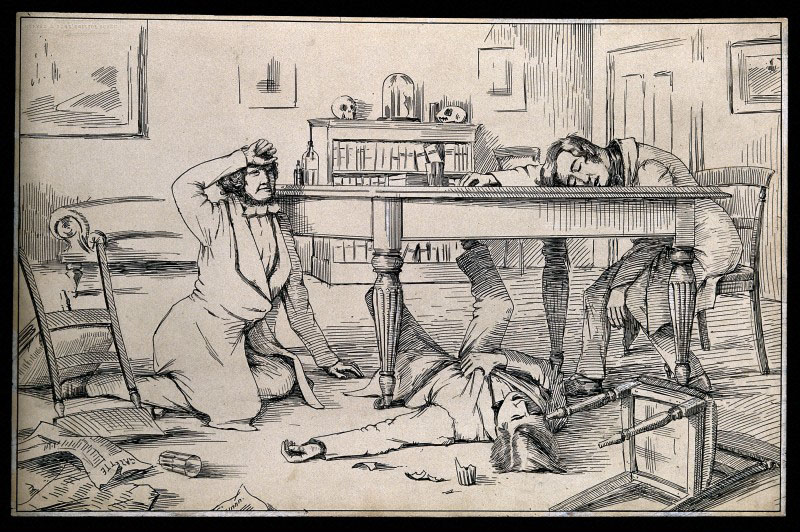

In 1847, a London obstetrician named James Simpson invited a few friends over for an experiment. He was interested in finding an anesthetic that could be used during difficult childbirth situations, especially those involving surgery. He had managed to obtain some chloroform from a local pharmacist. Sitting together in his dining room on the evening of November 4, 1847, Simpson and his friends inhaled the chloroform, began a cheerful conversation, and all fell unconscious.

The informality of this “experiment” appalls my modern science sensibilities. To try a new drug, unmeasured and unmonitored, on human subjects, is appalling. In retrospect, based on the account Simpson wrote of the event, it is lucky that the experimenters survived. Had they inhaled much more, they would have died….and chloroform would have been viewed as a substance too dangerous to use. On the other hand, had they inhaled less, they would not have succumbed and become unconscious. As it was, Simpson fortunately hit on an appropriate dose, and changed the face of obstetrics and surgery. It would be hard to estimate the number of lives saved through the medical procedures chloroform made possible from its first medical use in 1847 during the delivery of one of Simpson’s patients until its replacement in most countries a century later by more effective drugs with fewer side effects.

Scientific progress is often the result of both deliberate effort involving training and perseverance, and fortunate circumstance. Had Simpson’s dosages been even a bit different either way, the experiment would have “failed” to produce a result supporting chloroform’s use as a medical tool.