A thesis is a proposition for academic discussion. The scholastic method in medieval universities developed the disputation of a thesis to a high art, exemplified in many works including the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas. In a formal debate setting, the proponent would state the thesis and lay out the arguments in favor of it, citing pertinent authorities to back up his position. The opponent would answer each of these arguments, then lay out his own proposals in favor of the opposite view, to which the proponent might offer counterarguments.

This process of civil discourse allowed both sides to present their full positions, and all of the listeners a chance to hear all the arguments and make up their own minds.

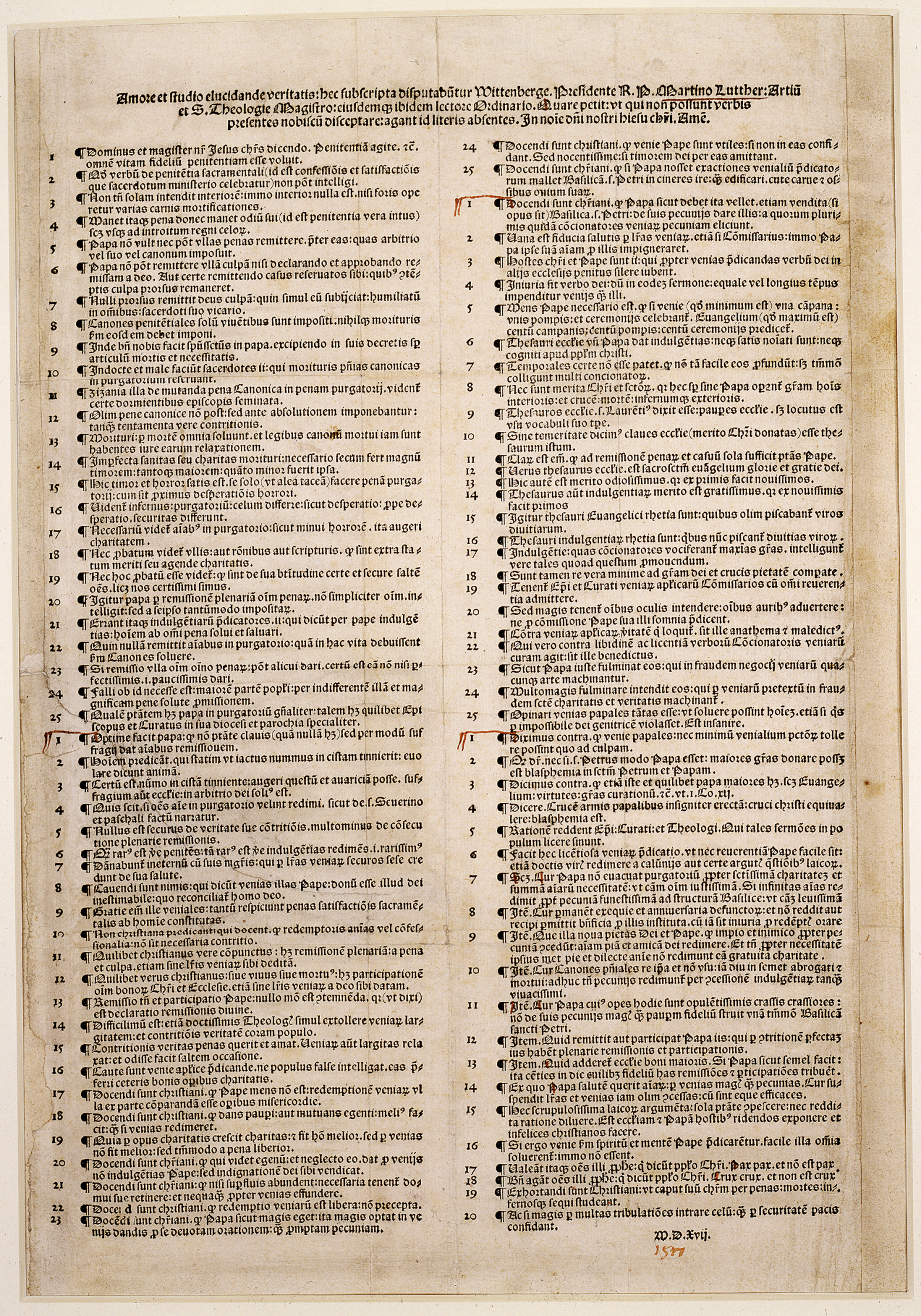

On October 31 (at least, according to popular accounts) in 1517, frustrated by what he considered flawed justifications for practices involving, among other things, the granting of indulgences, a professor of moral theology at the University of Wittenberg printed up ninety-five theses and nailed them to the door of All Saints Church in Wittenberg and sent a copy to the local Archbishop. Martin Luther’s intent was to create the venue for a debate. He invited other cities to participate in what was an accepted, traditional form of academic inquiry. His was not the first such list or invitation to debate the practice of indulgences: earlier that year, another professor at the University of Wittenberg, Andreas Karlstadt, had proposed a similar set of thesis on the same issues.

What is interesting to me here is that Luther set out to discuss the issue with his fellow clerics and professors: he did not issue an ultimatum, but invited others to take part in a process of discernment. But his action was perceived as provocative by some church officials, who moved to suppress Luther’s proposals; in effect, the Roman Curia asked Luther’s religious superiors to issue a gag order prohibiting him from preaching on the topic of indulgences (but not to stop preaching altogether). Other church officials saw Luther’s actions as an attack on the authority of the Papacy and responded with personal attacks on Luther, rather than addressing his proposals. The confrontation spiraled out of control into both church and political spheres.

The chance for a civil discussion about the nature of repentance and the practice of forgiveness, which we need so desperately to understand, was lost.