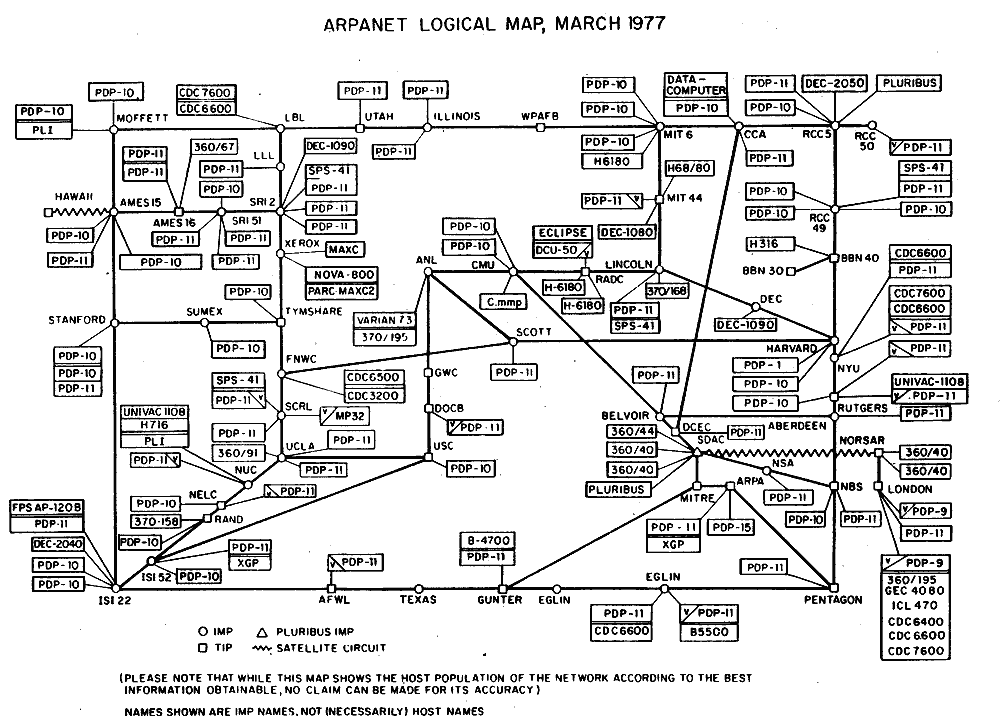

On October 29, 1969, around 10:30pm PST, Charley Kline, a student at UCLA using the SDS host computer in Boelter Hall, logged into the SDS 940 computer at the Stanford Research Center 350 miles away in the first successful ARPANET computer-to-computer transmission using a wide-area packet-switched network. Within a month, the UCLA-Stanford computers were permanently linked. By the end of the year, UC Santa Barbara’s IBM 360/75 and the University of Utah’s Dec PDP-10 had been added, creating a four-node core that would expand over the next decade to include every major educational, government, and military institution in the United States.

Arpanet was largely the brainchild of ARPA director Joseph Carl Licklider. Reviewing his own working routines, Licklider realized that far more of his time went into finding or obtaining information than into digesting it. He hoped to design a system that would engage computers to do the repetitive and detailed administrative tasks of information management and retrieval, freeing humans to think, imagine, and work creatively with each other.

By 1974, when I started working for NASA at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, run by CalTech, the computers used for processing images sent back by Earth-orbit satellites and later planetary missions were connected to the ARPANET with the Usenet discussion system. I still have printouts from exchanges that circulated the JPL and Rand systems, facilitating technical discussions and error tracing for software issues, but including a few movie reviews. Arpanet was the new coffee room, one that stretched across the country. It connected not just people who needed to work together, but people with shared interests in arts, entertainment, philosophy, science, and technology. Licklider’s vision of creative exchange and rapid information flow had become a reality, the nascent Internet.

The demand for increased storage and speed resulted in continuous innovations in computer hardware and network interfaces. The original interface message processors (IMPs) and connection protocols were replaced by new routers and a standardized transmission control protocol and internet protocol (TCP/IP) developed with National Science Foundation funds. NSFNET became the new Internet backbone, and the Arpanet was formally decommissioned in 1990.

Access to information is, as Licklider realized, insufficient in itself. We are still faced with the same issues that existed with the printed material he had found so time-consuming to consult or use. The internet may speed up our access to specific bits of information, but it cannot replace the critical analysis needed to determine whether the information we discover is reliable, or how we ought to use it.