In his October 22nd blog article, “Lifelong Learning”, Bruce McMenomy asked: “What does real lifelong learning look like when no one else is looking?” In answer he wrote: “I would say that the chief identifying characteristic is probably humility, a posture of respect for and submission to the truth. Genuine lifelong learning prioritizes the truth above anything having to do with oneself; it requires modesty about one’s own achievements, coupled with a fierce unwillingness to settle for a cheap simulacrum of learning for the sake of appearances.”

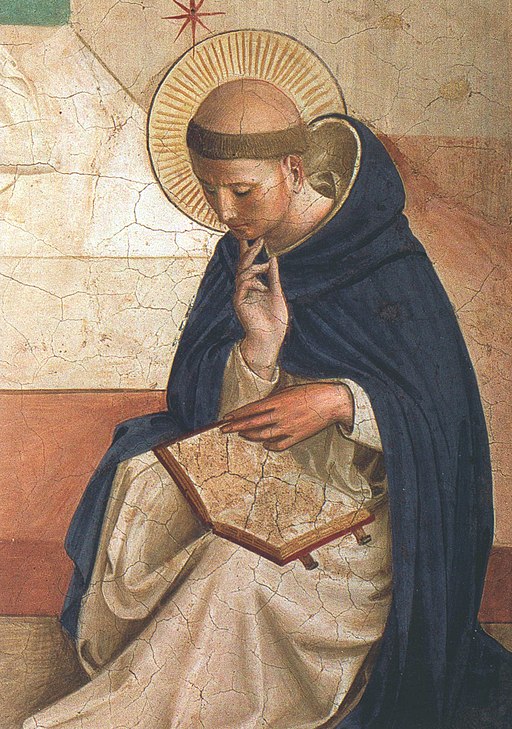

In the religious order to which I belong, the Order of Preachers – or more familiarly known as “the Dominicans” – lifelong learning is a spiritual discipline enjoined on all the friars. Our motto is “Veritas”, Truth, and we certainly agree with Dr. McMenomy that lifelong learning’s chief characteristic is humble submission to the truth. But with the Dominicans, a commitment to lifelong study has more to do with our usefulness to others than with “self-improvement”. It was contact with a civilization-killing heresy that spurred St. Dominic to found an Order with a universal license to preach the Gospel for the purpose of winning people over to the beauty of what is actually the case. For a Dominican friar to be thus useful in actuality entails the discipline both of continuous study over a lifetime as well as a radical submission to whatever proves true. In addition, yet another desirous quality for success in our stated purpose of preaching for the salvation of souls is the ability to take each individual seriously as an individual. This is commonly spoken of as “taking people where they are at”.

One of the favorite stories Dominicans like to tell about our founder relates an incident that occurred when he first accompanied his Bishop, Diego, in a preaching mission to reclaim southern France from the Albigensian heresy. They stopped at an inn where the proprietor was himself an Albigensian. While the bishop went to bed for some well-deserved sleep, his canon Dominic stayed up all night discussing their opposing doctrines. By dawn the innkeeper was convinced of the truth of the apostolic faith and renounced his Albigensian errors.

The virtue of humility gets a bad rap in our society, and humility before the truth, sadly, has few if any celebrity models. But consider the question, “Who is the real hero in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings?” Tolkien himself would have replied: Sam. At first he just seems to provide comic relief. But without his steadfast and determined loving friendship for Frodo, they would never have made it to Mt. Doom, Aragorn would never have taken up the kingship, and Middle Earth would not have gained freedom from Sauron’s evil — and far from humble — designs. True humility means acting out of an accurate assessment of who you are, neither inflated with pride nor oppressed by depression. With respect to humility before the truth, it means having an accurate assessment of what you actually know and the boundaries of your own ignorance.

One response

I think we’re substantially in agreement here, Fr. James. I suspect there is an organic connection between a genuine and humble commitment to the truth and being useful to others. Both pivot (to hearken back to Karl Oles’ take on it) on love. I have prioritized truth in terms of learning specifically because that‘s the part of it that can be discerned in the matter of the learning itself. Being useful to others is more contextual: it will be a good thing or a bad one depending on who those others are and what they’re up to (and also how one defines help).

Helping people is generally a good thing, but one would not want to help, for example, the assassin or the hit man in performing his task; obviously one could (in something like Platonic terms) parse that as being ultimately *unhelpful* to the practitioner, since it does not work for his or her moral good or the improvement of his soul.

As for Sam, I would largely agree, though I wonder whether the assessment is a simple one. I don’t think he’s the only hero or even the _primus inter pares_. There are several interconnected heroes in the book, all of whom are integral and necessary to the final victory over Sauron. All four of the hobbits play their critical roles; so also do Gandalf and Aragorn. For all his faults, so even does Boromir. Sam could not have done what he did solo; he required Frodo to be the primary Ring-bearer. Tolkien said a number of things about Sam in his letters, some of them less than complimentary. He notes particularly the scene in which Sam’s suspicion of Gollum (for all that it was selflessly motivated by his love for Frodo) helped push Gollum away from the light, so to speak. Tolkien himself pointed to that critical scene as one of the most challenging in the character arcs of the book.