It is with sincere sorrow that I note the passing of John Polkinghorne, on Tuesday last, March 9.

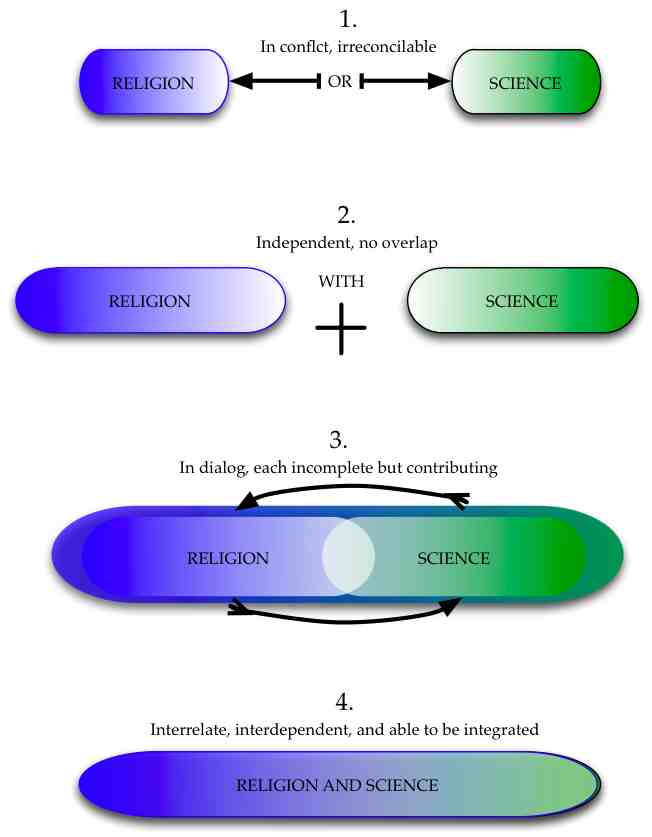

Many years ago, when I was first putting together the Scholars Online Natural Science course, I ran across a discussion of the possible relationships of science and religion. The author broke them down into four options: irreconcilable conflict, independently dealing with different domains, in dialogue and complementary but neither complete, and finally interdependent and moving toward integration into a single world view. It was a clear explication, and I summarized it and created a nice graphic for the first unit of the course. Hunting back through my notes some years later in preparation for a Lenten series on the relationship of science between science and religion, I realized that the original idea had come from John Polkinghorne.

In the course of a life spent with one foot in the church and one foot in the lab, one of the most frequent challenges I’ve heard is “How can you be a Christian and a scientist at the same time?” It didn’t matter whether I was in the church or the lab: the question came up with equal frequency in both places. The perception that the two modes of thought are irreconcilable is pervasive in American culture, backed by an equally pervasive conviction that scientists and theologians can have nothing to say to one another.

So it was with an incredible sense of relief that I discovered Polkinghorne’s works, for Polkinghorne is one of those Christian writers, like Francis Collins, who boasts impeccable scientific credentials. After studying physics and mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge, he worked with Murray Gell-Mann at CalTech, and eventually returned to Cambridge where his studies in particle physics contributed to the discovery of the quark. He did research at Princeton, UC Berkeley, Stanford, and CERN, and his discoveries are scattered through the physics journals of three decades.

But in 1979, having put a quarter of a century into the pursuit of modern physics, he re-entered Cambridge University as a student at Westcott House, and undertook a pursuit not of a different kind, for he was still in search of the truth, but in a different mode. He was ordained to the Anglican priesthood in 1982. From that time he held a number of theological appointments, including dean of Chapel at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, and he wrote constantly about the quest for truth, which in his view was a joint endeavor in which science and religion are not only complementary, but indispensable to one another. While he wrote for the general public, his works are not superficial; he’s not an “easy read” for a Sunday afternoon. It took me several weeks to work through the relatively short Science and Religion in Quest of Truth, notebook and pen in hand, but it was well worth the effort.

Polkinghorne was serious about establishing a common ground for all those who sincerely seek the truth. He believed that a complete integration of science and theology is possible when we recognize how similar the methods of science and theology actually are. He was also acutely aware that achieving this vision requires fundamental honesty and the humility to abandon allegiance to one or the other “cause”. Instead, we must be prepared to recognize the synthesis of the two voices speaking one truth, a position he rightly attributes to Galileo, who said in his letter to Benedetto Castelli, in 1613:

“For the Holy Scripture and nature both equally derive from the divine Word, the former as the dictation of the Holy Spirit, the latter as the most obedient executrix of God’s commands.”

In explaining his own work both scientific and theological, Polkinghorne said, “If we are seeking to serve the God of truth then we should really welcome truth from whatever source it comes. We shouldn’t fear the truth. Some of it will be from science, obviously, but by no means all of it. It will sometimes be perplexing, how this bit of truth relates to that bit of truth; we know that within science itself often enough and we find it outside of science as well. The crucial thing is to be honest.” (Faith of a Physicist , The Gifford Lectures, 1993-1994).

Seeking the truth is fundamental to our vision of Scholars Online. It is not always an easy road, and there is no single path to its final goal. But we can hope to help students along the way, with skills and tools for discernment, with insight into the experiences of those who have lived before, with encouragement from our own experience, and with the steadfast conviction that truth is worth pursuing, since that pursuit must perforce lead us to God, the source of all truth.

One response

Agree. I have been struck also by the fact that scientific reasoning and theological reasoning can be similar. For example, the scientist sees that light can be considered both a particle and a wave. He or she can’t imagine out how it could be both, but the behavior of light can be described in the abstract (mathematically) in a way that is logically consistent, even if unimaginable. Similarly, the theologian learns that God is both one and three. He or she can’t imagine how God could be both, but God’s activity can be described in the abstract (using the terms of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) in a way that is logically consistent, even if unimaginable. In both cases, the scientist/theologian respects the data in the sense that he or she is unwilling to omit any data just because the reality can’t be pictured.